The first time I slept on a stranger’s floor must have been in March 2020. I had just celebrated my twentieth birthday. Mini Tuesday was just around the corner. The outbreak of a weird new disease in Asia had canceled my spring break plans (budget backpacking in Thailand). Instead, a friend suggested I fly to Detroit to canvas for Bernie Sanders in the Michigan Primary, which was just a few days away. I said sure, and booked a $137 Spirit airlines flight departing that afternoon.

In Detroit, I spent 8 hours a day doing GOTV canvassing for Bernie. I talked to store clerks at halal markets in Hamtramck, I helped voters get registered at a bus stop on Eight Mile. I slept in a sleeping bag on someone’s floor, I slept four people to a hotel room in Dearborn, I slept in the guest bedroom of someone’s house in a neighborhood whose name I’ve forgotten.

Since then, I’ve slept on a lot of couches and shared hotel rooms, traveling across the country for my work as a labor organizer and a socialist. An attic guest bedroom in Minneapolis, an air mattress in Denver, a cot in Chicago.

In one form or another, this kind of accommodation is generally referred to as “solidarity housing.” Solidarity housing has been a small but important part of my life as an organizer. And in recent months, it’s been a reminder of everything we have to fight for.

Solidarity housing is typically a place to crash offered by a comrade. More often than not, it’s someone you barely know, offering you a free place to stay wherever you’ve been sent to organize.

It’s a small gesture that at the core of our movement is a willingness to fight for someone we don’t know. We will open our homes to them. We will fight for them and with them. And when we get tired, we will do our best to help them fight for someone else, too.

Why do we organize? Because we have no other choice.

It was not a metaphor when Rosa Luxemburg made her famous declaration that it’s either “socialism or barbarism.”

In recent months, we have been faced with growing barbarism. Attacks on public services, public-sector unions and federal workers, LGBTQ+ youth in schools and sports, immigrants of all statuses. The far-right has made significant gains both electorally, economically, and culturally; the re-election of Donald Trump is just one snapshot of a wave of ultra-right conservatism.

The wealthiest man in the world, Elon Musk, has effectively purchased the highest political office in the United States, granting himself billions in government contracts while cutting benefits to some of the most vulnerable. It’s an unveiling and an escalation of the problem that socialists have known all along: under capitalism, electoral democracy is plagued by the unequal power of the capitalist class in our society and state. In order to accomplish a truly democratic society, we will need to build a mass movement for democratic socialism and transform society from the bottom up.

How do we do that? We organize.

Though it may seem bleak now, the despair of the working class is one of the greatest weapons of the ruling class. Those in power rely on feelings of fear and hopelessness. They bombard us with executive actions that they know will be shot down by the courts, for the sole purpose of confusing and scaring us.

Our politics instead have to be built on hope. They have to be built on the idea that a better world is not only possible, but is necessary. Yet this necessary better world is also contingent; it depends on our willingness and ability to act.

Throughout history, many Marxists insisted on the idea that socialism was not only necessary but inevitable. They had a lot of different reasons for believing that — ones I won’t get into here. Karl Kautsky once argued that socialism may very well be inevitable, but it is a matter of achieving socialism “sooner or later.”

I don’t know if I think socialism is inevitable. But I also don’t know if I think there’s much of a “later” to wait for it to come.

As Marx wrote, “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please.” The capitalist class is hoping that we will throw up our hands and give up; that the fear instilled by their attacks on us is enough. But one of the greatest contributions of Marxism is the idea that while we are constrained by the conditions of class society, the conditions of the past, the material conditions of our everyday lives that make organizing so damn hard, we are makers, not subjects, of history.

It’s our historical task to organize.

Okay, how do we organize?

When I lead organizing meetings and workshops for rank and file union members, I always make sure to make one very important point: you are an organizer.

Our society is not structured to empower working people to think of themselves as people capable of making history. Recently, I was talking to workers in the middle of union contract negotiations at grocery stores in Southern California. One of these workers asked, “Why would the company listen to me? I’m just a nobody.”

Over the past several decades, labor unions have developed a thick layer of union bureaucrats. In some unions, these bureaucrats can earn over half a million dollars annually, paid for by the dues of the rank and file union members. Worst of all, the union bureaucracy has deeply entrenched in the minds of workers that organizing is a job description, not a verb.

But rank and file organizing is precisely what we need to fight back against the attacks on workers and some of the most vulnerable populations.

Workers hold unique power in society by holding the “lever” of the flow of capital in society. With one simple trick, workers can bring the machine to a screeching halt: the simple act of withholding their labor. The strike is the most powerful action workers can take.

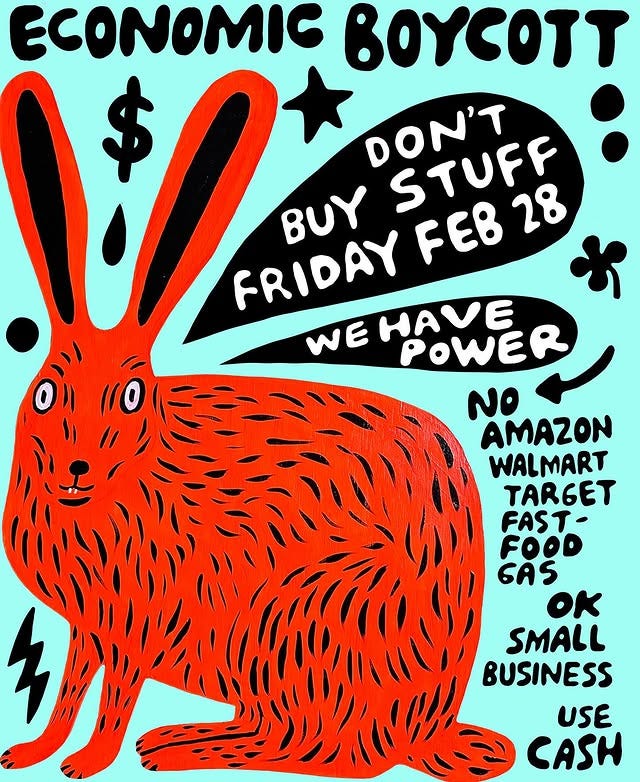

There have been attempts to assert power as consumers, such as the “economic blackout” on February 28th where people aimed to buy nothing to demonstrate, as claimed on the viral Instagram graphic, “We have power.” The popularity of unorganized economic boycotts is a testament to the weakness of the labor movement in comparison to the rest of US history.

Broad economic boycotts are popular precisely because they are easy and they have minimal to no stakes — especially if you can just wait to make your purchases tomorrow. This is markedly different from the consumer boycotts of the Civil Rights movement or the Delano grape boycotts, where targets were clear and specific, campaigns were long-term and sustained, and resistance was organized, in the form of walking miles on foot in caravans during the Montgomery bus boycotts, or the use of the grape boycotts as one of several strategies to support striking workers.

Economic boycotts are called for over social media today because our identities are much more wrapped up in being consumers than they are in being workers. Rebuilding the labor movement is a necessary step to moving beyond this impasse.

Organized labor is building towards critical actions on May Day 2025 and a potential general strike on May Day 2028. If you’re feeling hopeless these days, one of the most profound and brave acts of hopefulness you can take is to start getting involved in the labor movement.

If you’re already in a union, get involved. Find out who your shop steward and your union rep is. Assess your workplace — how present is the union? How involved and engaged are members? Do you know when general membership meetings are? What happens at them?

If your workplace doesn’t have a union, organize one! Reach out to the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC) for support. Brush up on organizing skills and what it takes to win a union drive with resources like Secrets of a Successful Organizer.

Rebuilding the labor movement is a long and arduous road. But it’s one of the only ones we’ve got ahead of us. The only way out is through.